On this cold, rainy Saturday, I attended my monthly writing group. I was excited to see large pieces of paper on our tables and curious about what we were going to do. I noticed some chalk pastels on another table and wondered if we were going to draw something to aid our writing.

I was horrified and disappointed when the group leader told us she wanted us to shut our eyes and draw to music. I have never enjoyed that process because I don’t relate to finding form in music and prefer to look when I’m creating something.

We were told we could choose a colour or close our eyes and let a colour choose us. I would have gone straight for anything pink-toned, but instead, I waved my hand a couple of times over the offered colours, hoping I had remembered well enough where the pinks were, and picked up the first chalk my fingers touched. To my deep disappointment, it was a very dark grey, similar to the little Ford Festiva I owned when we moved back to Western Australia from New South Wales.

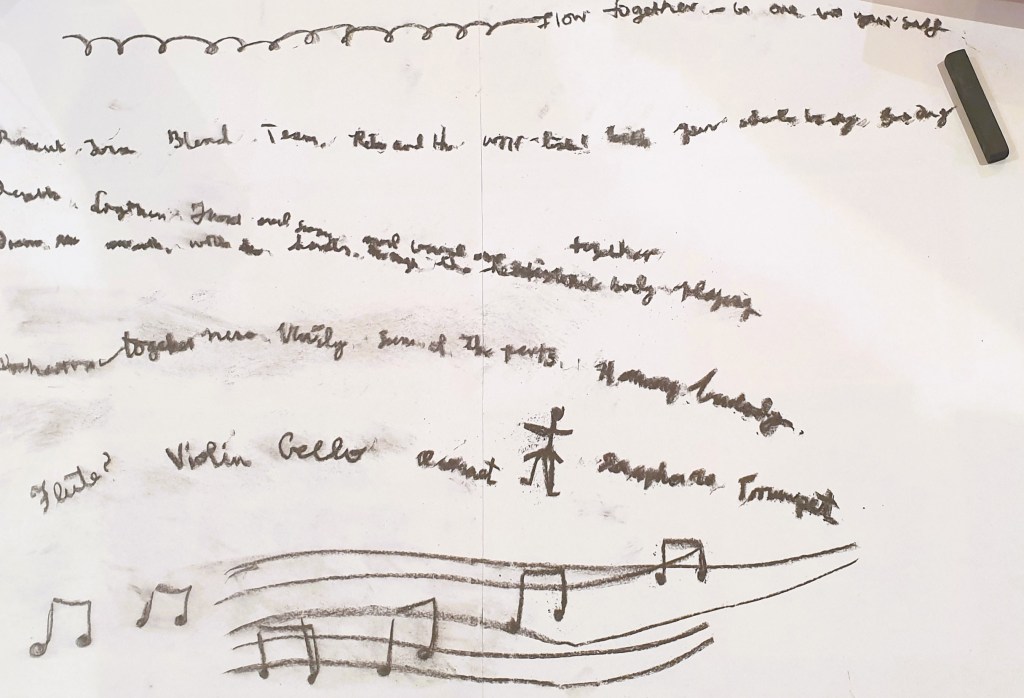

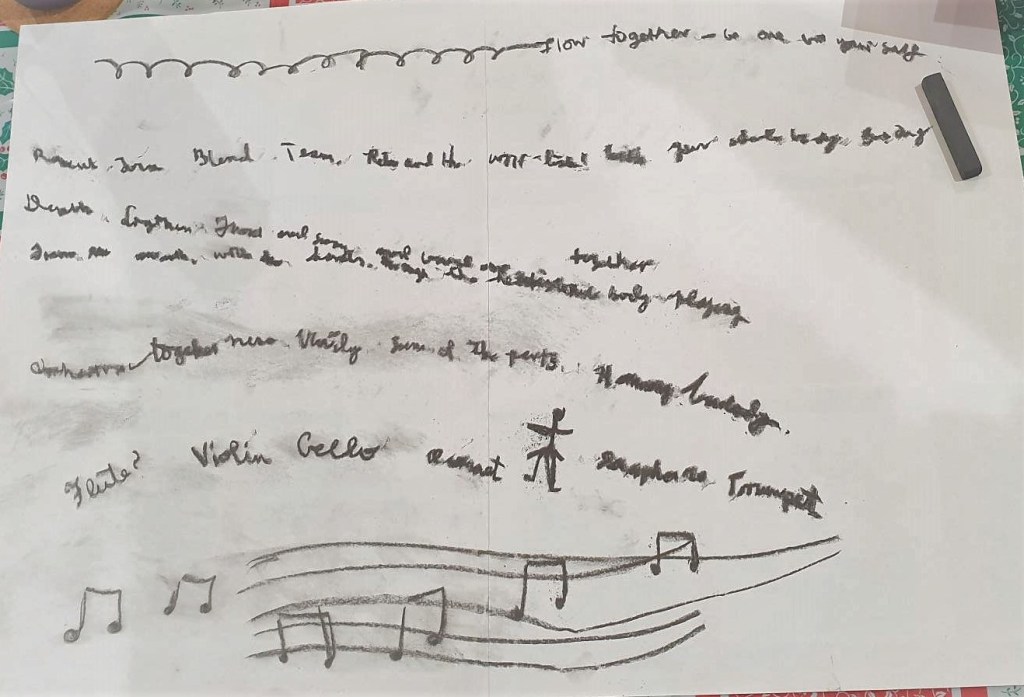

I felt as grumpy as the colour looked, but I chose not to change it. I then worked on the paper in front of me, eyes closed as instructed, for about ten minutes. When our time of torture was over, we were invited to write for 30 minutes about what we had drawn, if it spoke to us in any way. Below is my response in image and word.

DRAWING TO MUSIC

Ten minutes of hate, that’s what it became. I wanted the pink chalk. I love pinks – their rosy-cheeked happiness appeals to me, drawing me in. But my fingers chose grey – a shade so dark it was almost black. Perhaps that’s because my mind steered me in that direction, given I despise the nothingness of drawing to music. I didn’t enjoy it at seven years old, and I still don’t like it forty-six years later.

So, my work became black on white, austere, boring, lifeless. Around me, people swirled and danced in fuchsia, lime green and aquamarine. I couldn’t see where I was going – literally and figurately – so I felt adrift, baseless, without plan or purpose.

I was annoyed, and so I chose instead to draw the words – the instruments I could hear. I’m not musical enough to name them correctly, but I had a good guess. That high floating tune was a flute resting lightly against puckered lips, a gentle breath and nimble fingers bringing the silver tube to life. Next, the strains of a violin, mournful as the bow was drawn across the tight strings. A deeper tune now, not as silvery as a flute, but much lower than the violin. Probably a cello, its body gripped firmly between the cellist’s knees as their bow coaxed the strings to release its more guttural sounds.

At this point, while wondering how far into our time allocation we were and hoping it was nearly over, an image came to mind. A ballerina, arms raised, on pointe, stiff skirt spinning. How does a blinded artist, working with the dullness of grey on white, manage to portray such beauty and finesse? Ultimately, one doesn’t. Thus the graceful dancer leaping and twirling in my mind became a stick figure on the page – a parody of what I envisaged and longed to present.

Perhaps that is how my grandmother always felt. A creative individual, limited by the eyes that now only saw in light and dark, unable to identify individuals other than by their voices. She wrote regularly to us, her spidery, uneven, loosely formed writing instantly identifiable and almost impossible to decipher. She had been a poet in her younger days and, in all truth, probably still was. But for her, unless someone was willing to give of their time to scribe her words, her days of composing verse anywhere but in her mind had ended. What point in writing words on paper that she could not read over again to enjoy?

If she had been born now, instead of at the turn of the twentieth century, there would be ways she could continue to enjoy her craft – tape recordings, phone dictation, even voice-to-text writing so others could engage with the words she had produced and played with to enhance others understanding of what she saw. Did she still create, in her mind, speaking out words into the nothingness around her as she sat in her one-bedroom flat, close by and yet far enough away from the rest of the family who wanted her to be near but not too close in order to assuage their guilt at not visiting except once a week when the task could no longer be ignored? It was not her blindness they avoided – the paranoid schizophrenia that made her accuse even those voices she knew well of being another, come to harm her, was the real reason for their avoidance.

I cannot imagine being in her place- full of ideas, but nobody to speak them to, and no way to revisit them, without sight enough to read. I hope she did not feel as I did during this exercise – limited, frustrated, without purpose, unguided, and unable to check my progress and correct anything that hadn’t formed the way I intended it to.

I didn’t take my hand off the page, connected constantly to the chalk as it slid its way across the paper, my left hand dragging across my creation, blurring it and transferring its darkness to my skin. I would have happily worn the stain of pink. Instead, I turned grey.